By Prof. M. Izady

The vast Kurdish homeland consists of about 200,000 square miles of territory. Its area is roughly equal to that of France or of the states of California and New York combined.

Kurdistan straddles the mountainous northern boundaries of the Middle East, separating the region from the former Soviet Union. It resembles an inverted letter V, with the joint pointing in the direction of the Caucasus and the arms toward the Mediterranean Sea and the Persian Gulf.

In the absence of an independent state, Kurdistan is defined as the areas in which Kurds constitute an ethnic majority today. Kurdish ethnic domains border strategically on the territories of the three other major ethnic groups of the Middle East: the Arabs to the south, the Persians to the east, and the Turks to the west. In addition to these primary ethnic neighbors, there are many smaller ethnic groups whose territories border those of the Kurds, such as the Georgians (including the Lâz) and the Armenians to the north, the Azeris to the northeast, the Lurs to the southeast, and the Turkmens to the southwest.

The range of lands in which Kurdish populations have predominated has, historically, fluctuated. Kurdish ethnic territorial domains have contracted as much as they have expanded, depending on the demographic, historical, and economic circumstances of given regions of Kurdistan.

In the north of Kurdistan, Kurds now occupy almost half of what was traditionally the Armenian homeland, that is, the areas immediately around the shores and north of Lake Vân in modern Turkey. On the other hand, from the 9th to the 16th centuries, the western Kurdish lands of Pontus, Cappadocia, Commagene, and eastern Cilicia were gradually forfeited to the Byzantine Greeks, Syrian Aramaeans, and later the Turkmens and Turks. This last trend, however, has begun to reverse itself in the present century.

Vast areas of Kurdistan in the southern Zagros, stretching from the Kirmânshâh region to Shirâz (in Fârs/Pârs/Persis country) and beyond, have been gradually and permanently lost to the combination of the heavy northwestward emigration of Kurds and the ethnic metamorphosis of many Kurds into Lurs and others since the beginning of the 9th century AD. The assimilation process continues today and can, for example, be observed among the Laks, who, although they still speak a Kurdish dialect (see Laki) and practice a native Kurdish religion (see Yârsânism), have been more strongly associated with the neighboring Lurs than with other Kurds. The distinction between the Kurds and their ethnic neighbors remains most blurred in southern Kurdistan in the area where they neighbor the Lurs, that is, on the Hamadân-Kirmânshâh-llâm axis.

Since the 16th century, contiguous Kurdistan has been augmented by two large, detached enclaves of (mainly deported) Kurds. The central Anatolian enclave includes the area around the towns of Yunak, Haymâna, and Cihanbeyli/Jihânbeyli, south of the Turkish capital of Ankara (the site of ancient Cappadocia). It extends into the mountainous districts of north-central Anatolia (the site of ancient Pontus), where it is bounded by the towns of Tokat, Yozgat, Çorum, and Âmâsyâ in the Yisilirmâq river basin. The fast-expanding north-central Anatolian segment of the enclave now has more Kurds than the older segment in central Anatolia. It is doubtful that, except for some very small Dimili-speaking pockets, this colony harbors any of the ancient Pontian Kurds who lived here until the Byzantine deportations of the 9th century.

The north Khurasân enclave in eastern Iran is centered on the towns of Quchân and Bujnurd and came into existence primarily as a result of deportations and resettlements conducted from the 16th to the 18th centuries in Persia.

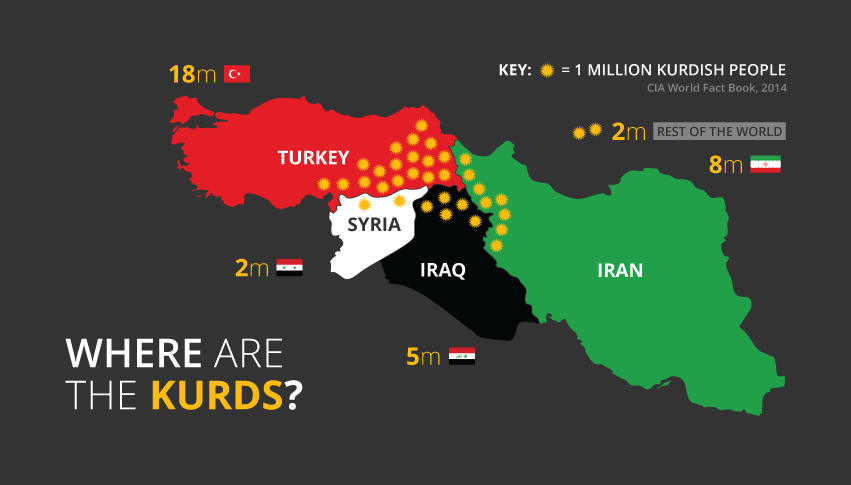

Since World War 1, Kurdistan has been divided among five sovereign states (see History), with the largest portions of Kurdish territory in Turkey (43%), followed by Iran (31%), Iraq (18%), Syria (6%), and the former Soviet Union (2%). These states have at various stages subdivided Kurdistan into a myriad of administrative units and provinces. Only in western Iran has the Kurdish historical name, even though corrupted, been preserved, in the province of “Kordestan,” with its capital at Sanandaj.

A rather peculiar and confusing by-product of the division of Kurdistan among contending states and geopolitical power blocs is its four time zones (five if Khurasân in Turkmenistan is also counted). The continental United States, 15 times larger than Kurdistan, also has four time zones. Geographically, Kurdistan fits perfectly into one time zone, 3 hours ahead of Greenwich, England. The standard – 3 hour time zone is defined as the area between 35 and 50 degrees east of Greenwich. With its western and eastern borders at, respectively, 36 and 49 degrees east, Kurdistan should naturally fall into a single time zone.

Sources: The Kurds, A Concise Handbook, By Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady, Dep. of Near Easter Languages and Civilazation Harvard University, USA, 1992

Further Readings and Bibliography: Map of Eastern Turkey in Asia, Syria, and Western Persia (Ethnographical) (London: Royal Geographic Society, 1906, updated in 1914), with fufl-color sheet map at 1:2,000,000 scale; Ethnographische Karte der Tijrkei: Vilayet Darstellung der amtlichen Tarkischen Statistik 1935 (Berlin: Presse E. Zagner, n.d.), with sheet map at 1:2,500,000 scale; S, 1. Bruk and V. S. Apenchenko, Atlas Narodov Mira (Moscow: Academy of Science, 1964); S.1. Bruk, Narody PeredneyAzii (Moscow: Ethnographical Institute, 1960), with sheet map at 1:5,000,000 scale; J. F. Bestor, “Ibe Kurds of Iranian Baluchistan: A Regional Elite,” unpublished masters thesis, based on the author’s field work (Montreal: McGill University, 1979); W. Barthold, An Historical Geography of Iran (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984); G. Le Strange, The Land5 of the Eastern Caliphate (London: Cass, 1966, reprint of the 1905 original); H.W. Hazard, Atlas of I51amic History (Prinecton: Princeton University Press, 1951); L. Nestmann, “Die ethnische Differenzierung der Bev61kerung der Osttiirkei in ihren sozialen Beziigen,” in Peter Andrews et al., Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey (Wiesbaden: Reichert, 1989); Annual Abstract of Statistics, 1970 (Baghdad: Government of Iraq, 1971); Statistical Abstract 1973 (Damascus: Government of Syria, 1973); Population Cen5u5 1970 (Damascus: Government of Syria, 1972); Captain Bertram Dickinson. “Journeys in Kurdistan,” Geographical journal 35 (1910), with map of Kurdistan at 1:2,000,000 scale; Captain F.R. Maunsefl “Kurdistan,” Geographical Journal 3-2 (1894), with map at 1:3,000,000 scale; Captain F.R. Maunsell “Central Kurdistan,” Geographical Journal 18-2 (1894), with map at 1: 1,000,000 scale; Lieut. Col. J. Shiel, “Notes on a journey from Tabriz, through Kurdistan via VAn, Bitlis, Se’ert and Erbfl, to Suldmaniyeh, in July and August 1836,” Journal of the Royal Geographical Societv 8 (1838), with map at 1:4,060,000 scale; T.F. Aristova and G.P. Vasfl’yeva, “Kurds of the Turkmen SSR,” Central Asian Review 13-4 (1965).

Reference: https://kurdistanica.com/401/boundaries-political-geography/